I had a bit of a flirtation with AI early on.

It was fun and exciting to play with it and see if I could push the limits of what I myself could do. I was inspired by Jonas Peterson – a photographer and an early Midjourney adopter who seemingly mastered the art of AI (and made a shit ton of money in the process; if I’m being honest with myself it is the money part was what mostly inspiring to me).

I played with ChatGPT to write bits of content and sales copy for my website, suggest course outlines or do research. I experimented with Midjourney, trying a new approach to my project Everything Was Forever. I wondered if I could imagine – and create – missing photographs from an old family album to maybe feel closer to the family I never knew (spoiler alert: it didn’t really work, but re-learning how to embroider and spending a lot of time making things with my hands made me feel like I’m channelling my great-grandmother more than any fake AI photographs ever could).

I stopped all of the above when I hit the wall of having to spend the time (and a lot of it) to learn how to get it do precisely what I wanted (ironically it actually was not that easy at all). I meant to get back to it when I had the brain space and the time – but then I started learning about real-world consequences of such frivolous AI usage, and decided I’m never going back.

That, and also AI being suddenly pushed on us from every direction, often without an opportunity to opt out, and – more recently – companies like Open AI and Google dropping their pledges not to use their technology for military purposes. Ouch.

I realise that many people don’t think twice about using AI for trivial things – just like I did to begin with. The technology is there, why not use it, right?

But there are so many problems with continuing to use AI technology (apart from supporting sinister companies that run it) that I don’t think get discussed nearly enough, and that includes our creative sector. I see many creatives being actively encouraged by their mentors and peers to use ChatGPT to help write funding applications, blog posts, newsletters and social media captions. Christie’s is hosting an AI “art” auction and Sotheby’s recently sold an “artwork” made by an AI robot for $1 million.

It breaks my heart and I just can’t not say something.

Environmental impact

Environmental impact of AI is very significant, and will only continue to grow.

Consider this:

It is estimated that it costs about 30 times as much energy to generate text in an AI “search overview” versus simply extracting it from a source as a traditional Google search does. Generating just two images with AI could use as much energy as the average smartphone charge, and every 10 to 50 responses from ChatGPT running GPT-3 evaporate the equivalent of a bottle of water to cool the AI’s servers.

According to the International Energy Agency, total electricity consumption from data centres could double from 2022 levels to 1,000 TWh (terawatt hours) in 2026, equivalent to the energy demand of a country of Japan. At the same time, both Google and Microsoft have stated their target of net zero by 2030 (which is already too little too late to prevent the most devastating effects of climate change) are threatened by increased data centre activity due to AI. Google alone has increased its greenhouse gas emissions by 48% since 2019 (Source: Guardian). Goldman Sachs research estimates that by 2033 Europe’s AI-driven power demand could grow by 40-50%, matching the current total consumption of Portugal, Greece, and the Netherlands combined.

And then there’s water use. According to research conducted by Pengfei Li, Jianyi Yang et al, “training the GPT-3 language model in Microsoft’s state-of-the-art U.S. data centres can directly evaporate 700,000 liters of clean freshwater”. The same study found that the global AI demand is projected to account for 4.2 – 6.6 billion cubic meters of water withdrawal in 2027, which is more than the total annual water withdrawal of 4-6 Denmarks or half of the annual water withdrawal of United Kingdom.

Scary stuff, right? But wait, there’s more.

Copyright infringement

In order for AI to do anything, it needs to be trained. And generative AI (including ChatGPT and Midjourney and all the rest of them) gets trained on the work of creative people – photographers, illustrators, artists, writers. Our work. If your work exists on the internet, the chances are it has already been scraped. And the higher your profile (and the more prolific you where with alt-text on your photographs to get found by search engines so you can actually get clients – oh the irony!) the more likely it is that your work has trained generative AI that has the potential to make techbroligarchs even more millions billions, and leave you in the red.

The thing is, not a single photographer, illustrator, artist, writer has ever been asked permission on whether their creative work could be used for such purposes or not. And not a single one of them (us) has ever been compensated for such usage.

As I write this, I observe that I never didn’t know that AI was using people’s work without permission or compensation. That is self-evident: all that generated stuff doesn’t come from nowhere. But it’s one thing to passively, theoretically know something and sort of ignore it, and another thing to actively consider the consequences and implications of such facts in real life terms, and act on such information. It’s just like when we continue buying stuff from Amazon even when we know we really shouldn’t, versus deciding to boycott it even if it’s not convenient for us.

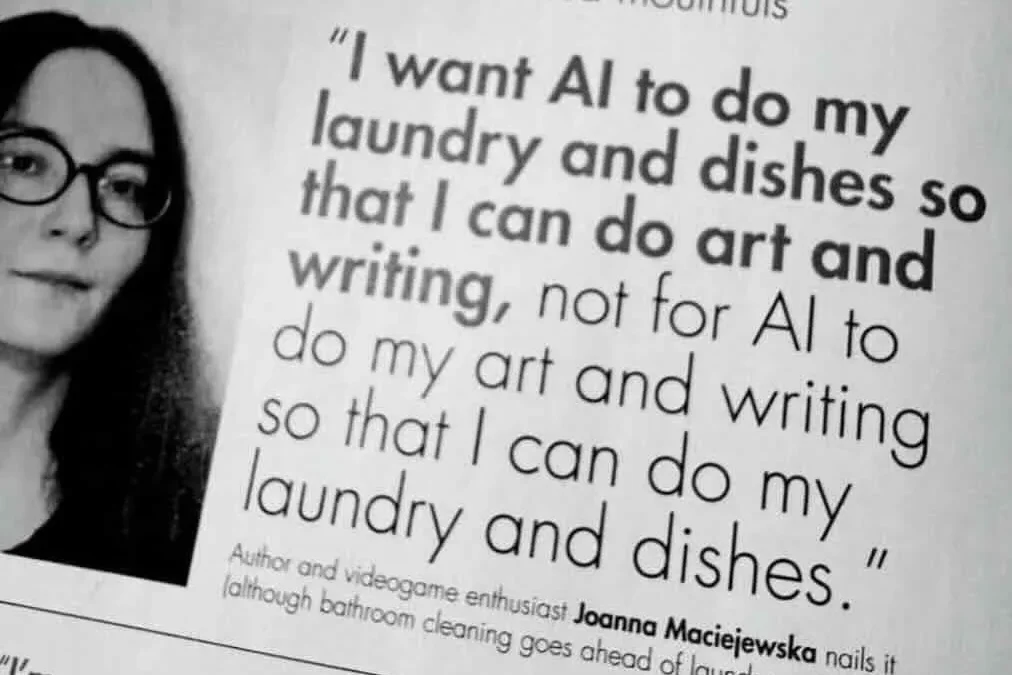

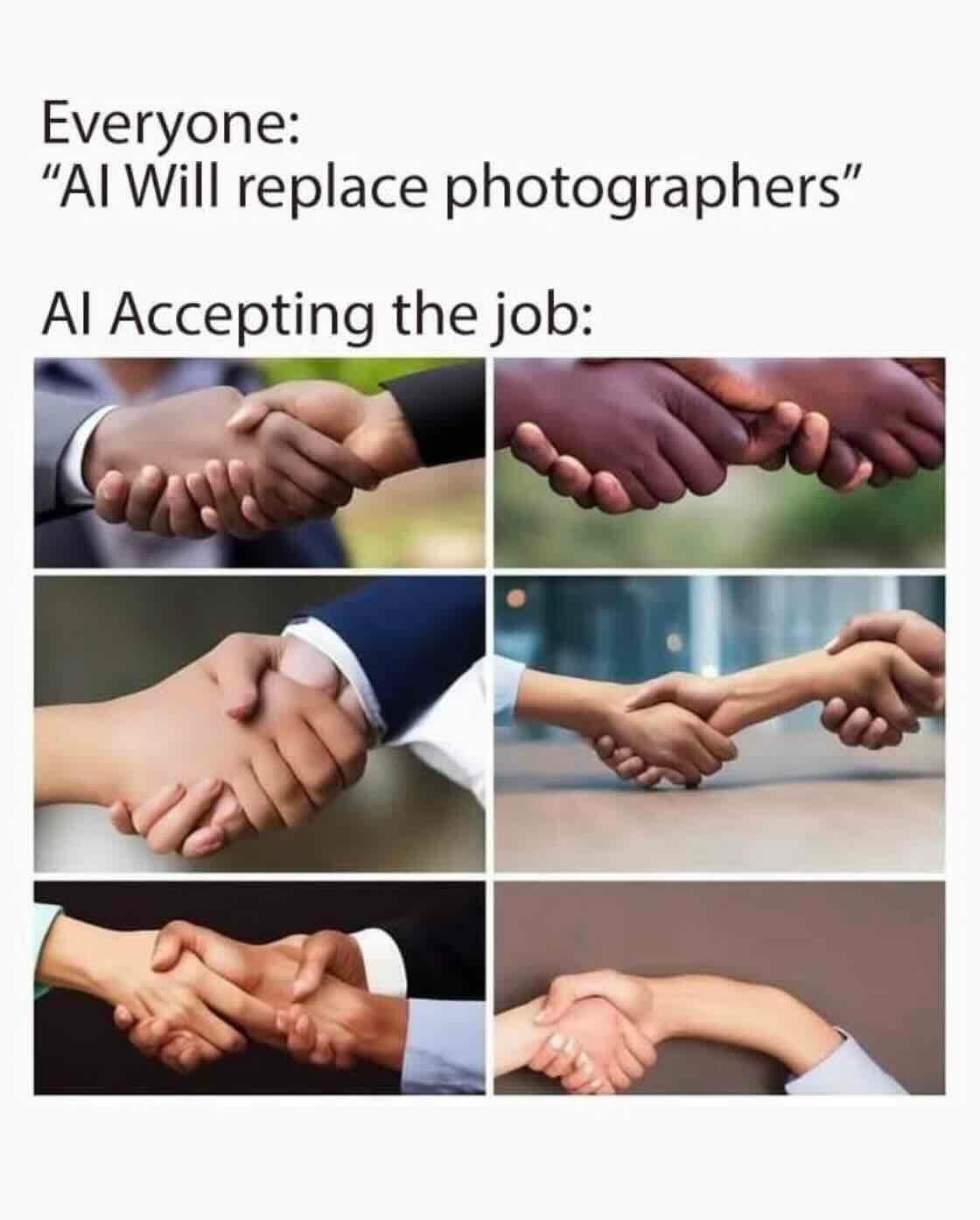

We often don’t actively consider the implications of something until it starts affecting us directly. I think many creators shrugged AI off initially as another dumb NTF-type thing that surely will never be able to generate anything meaningful (as evident from a meme below). I certainly was one of them. But as generative AI ingests more and more data, it gets better. I think it maybe even can now generate humans with exactly five fingers (shocker!).

But beyond that, one can now type in a Midjourney prompt, asking to generate art “in the style of”, or ask ChatGPT to write “in the voice of” and get a perfectly believable result.

Of course imitators have always existed, and as artists we often learn through imitation – but we only do that until we land on our own style, as is inevitable – for humans. Not to mention that a single person copying someone’s work is just not comparable in scale to the same thing being done on a corporate or even global level, automatically, and at lightning speed. To paraphrase

Austin Kleon, we steal like artists, not like machines.

(Fair warning: I’m about to get a bit nerdy – all those years at law school are demanding to be unleashed.)

As it stands right now, in most countries, creator’s copyright is protected by law from the moment the piece of work is created. That right is automatic, doesn’t require registration or opt-in, and lasts a lifetime, plus a number of years after the author’s death.

In most legal systems reasonable exceptions to copyright exist – for example when the material is used for studying or teaching, certain non-commercial purposes and even parody. In most cases, such uses must actively acknowledge (credit) the creator.

In the UK and US, those exceptions to copyright are further underpinned by a concept of “fair use” (US) or “fair dealing” (UK). There is no concrete definition of what exactly constitutes fair use, and it’s often left to the courts to decide what constitutes “fair”. The following will be considered when deciding whether the use of copyrighted works is “fair”:

- Is the use commercial? Does using the work affect the market for the original work? Would the copyright owner lose revenue due to the use of their work? If the answer to any of the above is “yes”, the use is unlikely to be considered fair.

- Some jurisdictions may also look at the nature of the work being used. Someone using bits of factual information from a book is more likely to be considered fair, as opposed to using a creative or imaginative original piece of art or writing.

- How much work is used? Is the amount of the work taken reasonable and appropriate? Was it necessary to use the amount that was taken? Usually only part of a work may be used for it to be considered “fair” (that’s why you’ll find many YouTubers using only very short clips of other people’s work, or collage artists being able to use existing works to create something new – it gets them as close to “fair use” as they can).

If you consider the list above, does it look like training AI systems like Midjourney or ChatGPT fall under any of these “fair use” exceptions? It doesn’t take a genius – or a law degree – to see that it doesn’t. Equally, as artists and creators, if we value our own copyright we must apply that same logic to works by other creators and respect it – and that includes using it “second hand” so to speak, through generative AI results.

Yet our governments are likely to be under a lot of pressure from tech companies to bring in new exceptions to copyright law, allowing unlimited and free data mining and scraping. They have been doing it for years, and there are currently a number of lawsuits in the works about exactly that.

The UK government is currently conducting a consultation, part of which is determining whether commercial AI training should become exception to copyright. And their stated preferred option is to automatically opt everyone’s work IN unless you opt-out – a mechanism that any creative can tell you is unworkable and is going to lead to exploitation of most artists.

The deadline to respond to the consultation is February 25, 2025. If you can, write to your MP, particularly if they are Labour. Creative Rights in AI coalition has put together a template you can use – or feel free to lift any of the points I outlined here, not forgetting to personalise it and state how such legislation would affect you, personally.

Dumbing us down

I notice, in retrospect, that my most “dry” creative period coincided with my active use of AI. I seemed to have hit the wall with my own writing and struggled to write original content, at time genuinely feeling like my head was empty of thoughts.

But Instead of taking myself for a walk in the fresh air or for a swim in the pool or just standing in the shower for 10 minutes – something that in the past has always reliably generated new ideas in my head – I would instead turn to ChatGPT and ask it to write the thing for me.

Looking back, I see how this reliance on AI and rapidly acquired feeling of inadequacy – learned helplessness? – was dumbing me down, visibly, in real time.

And don’t forget that that generative AI like ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini are not actually search engines, they are language models. They predict what words should be generated, and in what order, based on the prompt they are given, and it has gotten things wrong – very wrong – in the past. I have first hand experience of ChatGPT making up information when I asked it to find some quotes to support a piece of my writing (when caught and challenged, it apologised, using the “I’m only a humble language model, I don’t actually know anything” excuse) or to transcribe a bit of audio (it invented the whole dialogue while weirdly making it loosely relate to what the audio was actually about).

YouTube is full of videos of Google AI giving very, very bad advice (like “geologists recommend eating at least one rock per day”) and there was even a lawyer in Australia who got caught using ChatGPT because it literally invented non-existing case law.

Doesn’t being told that “you don’t need to think, the machine knows best” and trusting what the machine says, without engaging in critical thinking, give you distinct Orwellian vibes?

So what can you do?

AI technology is not all bad (but when it’s bad, it like really, really bad ). It can be used for good and do things that humans can’t (like identifying early cancer or analysing huge swathes of data that would otherwise take humans years to get through).

Some might argue (and they totally do) that the flipside of this increased energy use and compromises in copyright law, even when it comes to everyday use, is that AI is supposed to be freeing us all up to do other things – and lead to more economic growth.

There are (at least) two faults with this thinking.

First, if you consider all the technological advances that already have happened in the 20th and 21st centuries, we should all be working 15 hour work weeks and living our best lives, helping our communities thrive, tending to mother Earth and making art. Yet all these advancements only created more inequality in the long run, making us work even longer hours, glued to our technology – because, capitalism. If you’re interested to learn more about why this is, I can highly recommend Bullsh*t Jobs by David Graeber – a great book based on actual anthropological research.

And second, more growth is not the answer to humanity’s woes and the polycrisis we presently find ourselves in. We need to become more mindful about how we use technology and not take what we don’t actually need. It gets to the wider issue of using less in general as the only way out of the climate crisis – less energy, less stuff, less consumption. Jason Hickel, whose book Less is More I’m currently reading, writes and talks brilliantly about all of it, and so does Robin Wall Kimmerer in Serviceberry.

While we can’t really affect governmental and corporate policies, we do have quite a lot of power as consumers and internet users. So here are some simple, practical steps that I am taking to avoid using AI as much as possible:

Just decide not to use generative AI.

Yes, it’s that simple. Boycott it. You don’t need it. You will remember how to write stuff on your own and do your own Google searches, trust me.

What’s more, people have gotten very good at spotting AI-generated content, be it graphics or an email. It reeks of unauthentic and disingenuous, if not completely fake and untrustworthy, and that’s not how you want to be perceived. Far better to sound like yourself, with imperfect sentences and quirky turns of phrases that are your own.

And if writing is really not your forte, ask a friend for help editing an important email or a report. Fork AI, we have to get back to helping each other.

Use “-ai” when you use Google search – or just swear at it!

Currently, there doesn’t seem to be a way to opt-out of AI generated search result if you use Google (there are of course alternative search engines like DuckDuckGo and Ecosia but I know how hard it is to switch over from Google; I’m taking it one step at a time; in fact just writing this down prompted me to switch my default search engine to Ecosia, no AI results in sight).

But if you type “-ai” (without the quotation marks) at the end of any given Google search, the automatic AI-generated search result overview, the one that uses all the water and energy for no good reason, will not be served. The trick is getting into the habit of doing it every time, and not succumbing to the autocomplete on the search query.

My 14yo also tells me that if you type in swear words into your search query, an AI result will not be displayed. That’s very cathartic, right?

Use tools to protect yourself from image data scrapping by AI.

If you’re a photographer or a visual artist, you can start using free software Glaze and Nightshade to protect your digital images from being identified by machines, scraped and used in generative-AI programs (however if your images have already been scraped there’s nothing else you can do – which is why it’s so important to push our governments to make AI companies pay).

Glaze is a “cloaking” tool and it “cloaks” images so that AI models incorrectly learn the unique features that define an artist’s style, thwarting subsequent efforts to generate artificial plagiarisms. Nightshade is a “data-poisoning” tool that messes up training data in ways that could cause serious damage to image-generating AI models. It effectively adds invisible changes to the pixels in the artworks before uploading them online, and that can cause the AI generating models to break in chaotic and unpredictable ways.

Unfortunately, there are not very many protections for writers as of right now. If you want to go fully nuclear, you can disallow AI crawlers from accessing your website completely, but it will also prevent you being found in search engines, so it is not a sustainable option in my opinion. Neither is turning your text into JPEGs as it will make your website inaccessible to users who rely on text-to-speech.

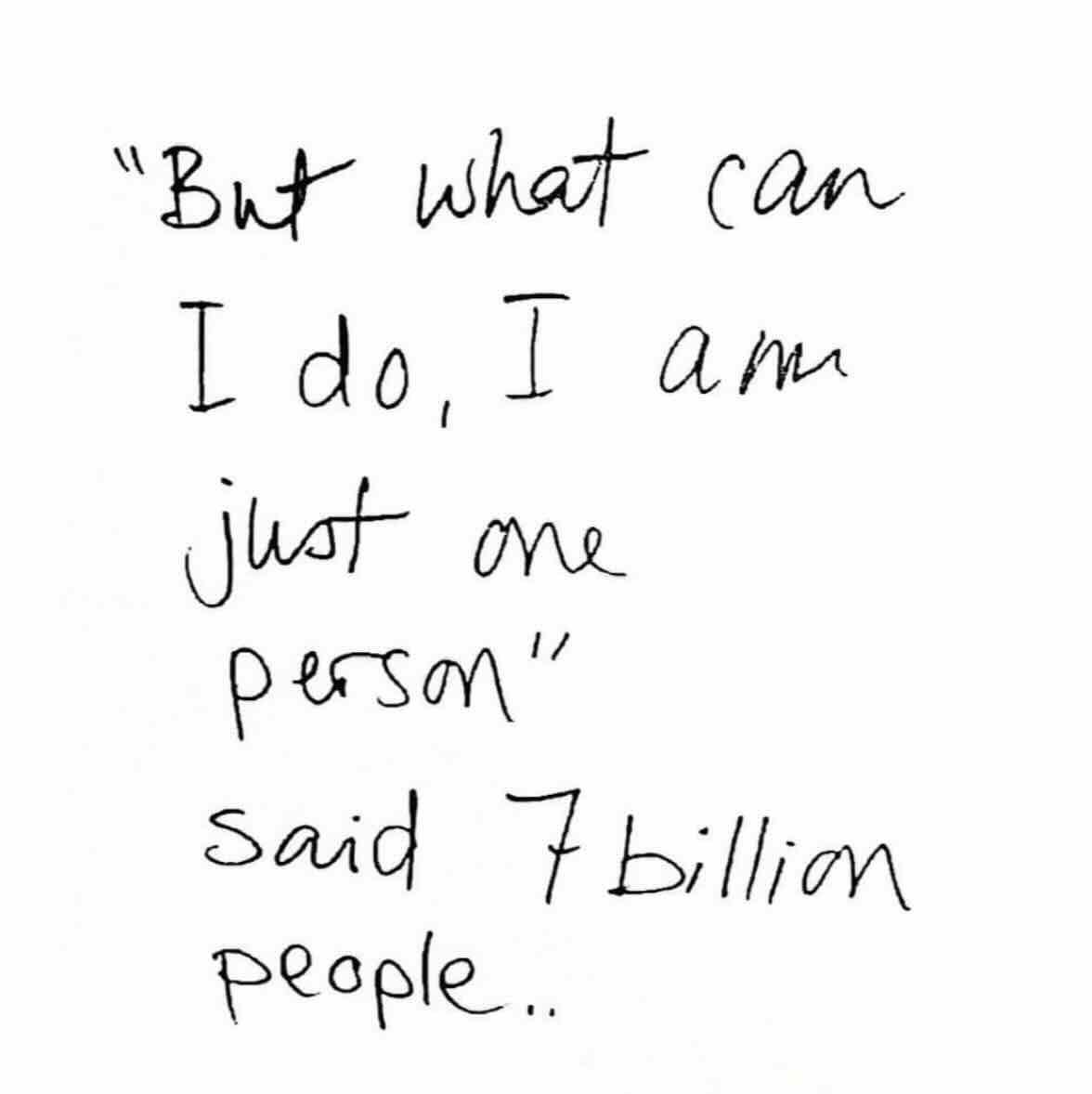

Finally, talk to others. We don’t talk to each other nearly enough.

See someone promoting the “benefits” of AI? Give them the facts. Many people have genuinely no idea of all the issues and problems AI creates. I really believe that when it comes to this, knowing what it actually costs will make people rethink their relationship with – at the very least – casual AI usage.

Phew, that was a long one and took me ages to put together. I hope it was useful. If you spotted any inaccuracies in the data I quoted, let me know. Equally, do share your own experiences and tips of getting away from AI – just shoot me an email.