I’m staring at a blank page today. I’m not quite sure what I want to write about. I have so many drafts and half-started essays, all of them competing for my attention. It frustrates me.

Should I write about walking the tightrope of a public creative practice, and the dangers of seeking out inspiration and feedback before your ideas have fully formed? Or about this beautiful ancient lake Nero that is said to hold untold treasures in its silty, unexplored depths? Or the violent language of photography and business that we use, unthinking? Or maybe about the haul of books I brought over from the recent trip to the motherland – the encyclopaedia of Slavic folklore, a book on photographic propaganda from the 1970s, and old regional embroidery guides – all found in second-hand book stores that at once felt like home and a treasure trove full of surprises?

As I write these words, trying to brute-force my way through the writer’s block – no, writer’s overwhelm – my teenager pops his head in.

“I have an idea. Hear me out.” He is full of ideas, always dreaming things up, building new worlds in his head. “Gods don’t have emotions so they created demi-gods to help them better understand the human world.”

He is world-building. His imagination is endless and, at times, confusing to me. I struggle to keep track.

“Is there a gremlin in your head that juggles different worlds so you don’t forget what belongs to what?”, I joke, maybe wishing for the same gremlin to help me control my own chaos of ideas.

We are very alike, he and I. Both with more ideas than we have realistically time for (hello, undiagnosed ADHD), except I get frustrated with myself and resent that I can’t write a hundred books and dive deep into a thousand topics to research, while he is quite happy to let his little brain gremlin juggle the imaginary multiverse and enjoy the very act of coming up with ideas. I think he should write a book (or five), start a blog, do something – but he doesn’t feel the need to turn them into any thing, share with anyone (but me) or do anything particular with them. His creativity has not yet been coopted.

“Yes, I do. It’s his job, okay?”. He disappears again, back to his imagined worlds.

I return to my own writing.

***

I never knew lake Nero even existed. And yet here it was, its calm, flat surface stretching in front of me, calling me in for a swim, whispering secrets in the forgotten language of the Merya people.

A swim would be foolhardy, I discover. Despite appearances, the lake is only about 2 meters deep in most places, and its bottom is covered with a millennia-old layer of silt, making it impossible to enter it from the shore, and unsafe to swim in. People speak of the “Nero monster”, a creature that drags people down into the unexplored depths. The legends are probably true – except it’s not the monster, but the silt itself that takes reckless souls under. Locals don’t swim in this lake, even in hot weather.

Other legends talk of untold treasures buried at the bottom of the lake – and even a whole town. Some of it probably also true: as the Mongol invasion swept through this area of Russia in the 13th century, it is likely that the local monks threw their golden crosses and ceremonial cups encrusted with precious stones into the lake. Archeological digs are near impossible here, but old coins and everyday objects sometimes wash up on the shore, hinting at what is still hidden beneath.

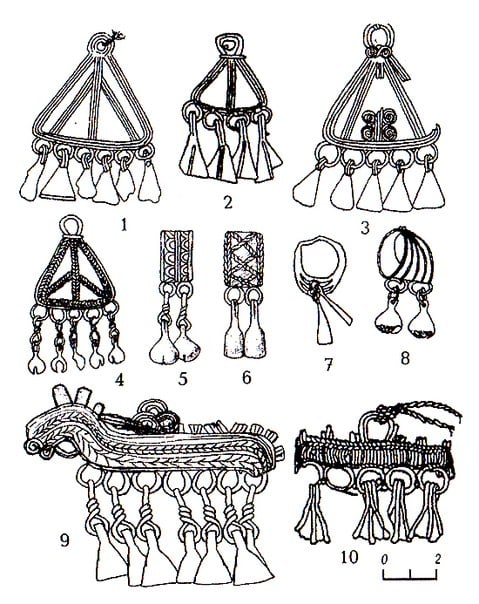

The Merya – ancient Finno-Ugric people of the area – have lived on the shores of lake Nero as early as the 7th century BCE, and left behind remains of their fortified trading centres, intricate jewellery and names for rivers and lakes – but no recorded language. They were later absorbed by the incoming Slavic tribes, and few traces of their way of life remain (although you can still recognise elements of the Merya decorative culture in traditional Russian window frame designs). There has been a recent Merya revival, with some locals trying to reignite the old pagan traditions, reconnecting to their ancient heritage and culture. I’m glad of it.

(Today in Russia, over three million people identify themselves as Finno-Ugric, among them Karelian, Sami, Udmurt and others. Some indigenous cultures faired better over the course of history, but many traditions have been irreversibly lost – or purposefully eradicated).

There’s so much we, as Russians, don’t know about our own history and heritage. History that has been re-written again and again, traditions and facts hidden, twisted, discarded, hierarchy of peoples instituted.

Paganism replaced with Christianity and old traditions forbidden, Christianity blown up (literally, with countless ancient churches demolished) and replaced with militant atheism and the belief that men can bend nature to their will (look up Northern river reversal project, it boggles the mind).

I know it only too well from looking into my own family tree, learning things I was never taught, unlearning things I never thought to question, drawing parallels between the past and the present – in Russia and beyond.

This is what visiting lake Nero – and the ancient city of Rostov that stands on its shores – was about, too: a research trip retracing the steps of my great-grandfather – a man who keeps giving me more questions than answers, but gifting me the opportunity to learn more about my own history and heritage, to remember who I am and where I came from.

It seeps into my creative practice in untold ways, and I’ll write more about it in the future.